Colorado search and rescue teams: Meet your friendly neighborhood superheroes

Colorado search and rescue teams are saving lives under the radar

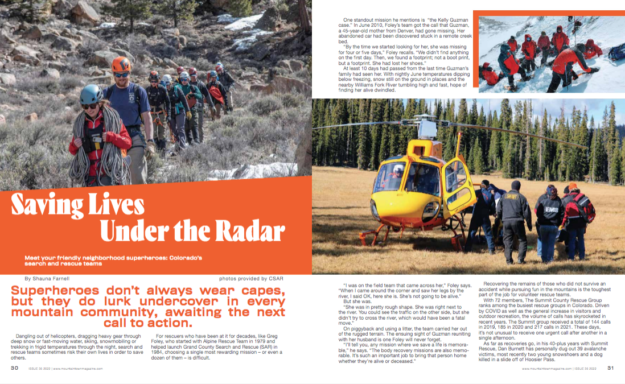

Superheroes don’t always wear capes, but they do lurk undercover in every mountain community, awaiting the next call to action.

Dangling out of helicopters, dragging heavy gear through deep snow or fast-moving water, skiing, snowmobiling or trekking in frigid temperatures through the night, search and rescue teams sometimes risk their own lives in order to save others.

For rescuers who have been at it for decades, like Greg Foley, who started with Alpine Rescue Team in 1979 and helped launch Grand County Search and Rescue (SAR) in 1984, choosing a single most rewarding mission – or even a dozen of them – is difficult.

One standout mission he mentions is “the Kelly Guzman case.” In June 2010, Foley’s team got the call that Guzman, a 45-year-old mother from Denver, had gone missing. Her abandoned car had been discovered stuck in a remote creek bed.

“By the time we started looking for her, she was missing for four or five days,” Foley recalls. “We didn’t find anything on the first day. Then, we found a footprint; not a boot print, but a footprint. She had lost her shoes.”

At least 10 days had passed from the last time Guzman’s family had seen her. With nightly June temperatures dipping below freezing, snow still on the ground in places and the nearby Williams Fork River tumbling high and fast, hope of finding her alive dwindled.

“I was on the field team that came across her,” Foley says. “When I came around the corner and saw her legs by the river, I said OK, here she is. She’s not going to be alive.”

But she was.

“She was in pretty rough shape. She was right next to the river. You could see the traffic on the other side, but she didn’t try to cross the river, which would have been a fatal move.”

On piggyback and using a litter, the team carried her out of the rugged terrain. The ensuing sight of Guzman reuniting with her husband is one Foley will never forget.

“I’ll tell you, any mission where we save a life is memorable,” he says. “The body recovery missions are also memorable. It’s such an important job to bring that person home whether they’re alive or deceased.”

~ Greg Foley

Recovering the remains of those who did not survive an accident while pursuing fun in the mountains is the toughest part of the job for volunteer rescue teams.

With 72 members, The Summit County Rescue Group ranks among the busiest rescue groups in Colorado. Driven by COVID as well as the general increase in visitors and outdoor recreation, the volume of calls has skyrocketed in recent years. The Summit group received a total of 144 calls in 2019, 185 in 2020 and 217 calls in 2021. These days, it’s not unusual to receive one urgent call after another in a single afternoon.

As far as recoveries go, in his 40-plus years with Summit Rescue, Dan Burnett has personally dug out 39 avalanche victims, most recently two young snowshoers and a dog killed in a slide off of Hoosier Pass.

“When you’re recovering the bodies of valuable humans that have died in the mountains, your hands feel like they’re anointed somehow because they’re the hands of loved ones who can’t be there to pick up their friend or loved one,” Burnett says. “You feel like your hands are the hands of hundreds of people.”

This connection of hands is less figurative in one of Dale Atkins’ most memorable missions. Atkins started with the Alpine Rescue Group, based in Evergreen, in the 1970s. He was a 14-year-old junior member when he was among a group sent to search for a 3-year-old girl who had wandered from her home in Idaho Springs one rainy afternoon.

“We were put into field teams, tasked to search a hillside and a drainage,” Atkins recalls. “We happened to go into the right place at the right time. Our group found her.”

The little girl was cold, but otherwise in good spirits.

“We walked her out. She took turns holding hands with the half dozen of us on the team.

She held my hand the same way my littlest sister did, hanging onto my pinky finger. Being one of the youngest in the group, I watched as our mission leaders turned her over to mom and dad with a sheriff’s deputy. Watching that was a beautiful thing, even for a squirrely teenager. I would say that’s the hook that has kept me in it over the years,” Atkins says.

As a young boy, Atkins was inspired to join Alpine Rescue after losing his father in a private plane crash and realized the impact rescuers could make in such a situation. Some of his time with Alpine Rescue, which works with the Army National Guard to enlist powerful helicopters for special missions in Colorado’s unique high elevation and thin air, has been spent conducting hoist rescues. Requiring intensive training, hoist rescues involve dropping out of a Black Hawk helicopter that is often hovering thousands of feet above the ground, using a rope and equipment to rescue injured individuals in precarious locations that cannot otherwise be reached.

Technology, including cell phones and GPS tools, have made such rescues much more successful. Atkins recalls two missions, nearly 40 years apart, on the notoriously deadly, 14,203-foot Crestone Needle in the Sangre de Cristo Range. The first involved a solo climber in the 1980s who had disappeared. Atkins and his team searched for five days without finding him. Then a group of climbers came across his body in a remote, hard-to-reach area where he had fallen off of the Needle.

“The recovery took another four days over two weekends. The weather conspired against us,” Atkins recalls. “Here we are 40 years later and because of all the technologies and our increased use of helicopters, we rescued an injured climber and his partner from a similar place and everybody was home by lunchtime.”

In this 2020 incident, the two climbers were scaling a technical route on the Crestone Needle when one climber fell about 30 feet, landing – luckily – on a sloping, snow-covered ledge. He had badly injured his ankle. It was about 4 p.m. and the climbers spent several hours trying to come up with solutions and ended up calling 911 at some point in the night. The call went to local rescue teams, which were already spread thin, then went through the Colorado Search and Rescue Association, which dispatched Alpine Rescue, a national guard helicopter with pilot, two soldiers, Atkins and teammate Mike Griffin.

For this mission, Atkins was the one “at the end of the rope.” As the helicopter hovered a few yards from the knife-like walls of the Needle and surrounding cliffs, the green and brown sprawl of land below resembled what one sees from an airplane window. Atkins maneuvered into the open sky on a harness and rope and was lowered down to the ledge, where he quickly connected one climber into a harness to fly to safety and then returned for the other.

See Atkins’ helmet cam footage:

“Both of these fellows were really appreciative,” Atkins says. “The injured fellow worked on his climbing, went back last summer and finished the route.”

~Dale Atkins

He found this deeply validating. “It’s very rewarding to help somebody, whether it’s minor or someone has had a horrible accident,” Atkins says.

“There’s great satisfaction working together with a team. When we respond to something, the entire team is bringing this huge wealth of skills and knowledge to someone having a bad day in the mountains.”

~ Dale Atkins

The team dynamic is the first thing rescuers name as the key ingredient to a successful mission. Individually, however, there is also a common thread that binds these superheroes together.

“Most people involved with mountain rescue, deep down inside there’s a compassionate part of their heart and soul,” says Scott Messina, a 35-year member of Mountain Rescue Aspen. “They want to help. If you look at a mountain rescuer, they’re a Jack or Jill of all trades – a good avy person, a good mountaineer – but compassion is a big part of it.”

According to Public Information Officer Anna DeBattiste of Colorado Search and Rescue Association and Summit County Rescue Group, there are roughly 2,800 rescue volunteers throughout Colorado, each of whom spends an average of $1,587 a year of their own money on gear, training, and travel. Search and Rescue teams are largely funded by donations and fundraising.

To learn more about local teams or to donate, visit Coloradosar.org.

From all of us at Mountain Town Magazine, we appreciate every single one of you involved with Colorado Search and Rescue. A sincere thank you.

Story Sponsored by

MTN Town Media Productions | Celebrating the Colorado mountain lifestyle

Copyright 2022 MTN Town Media Productions all rights reserved.